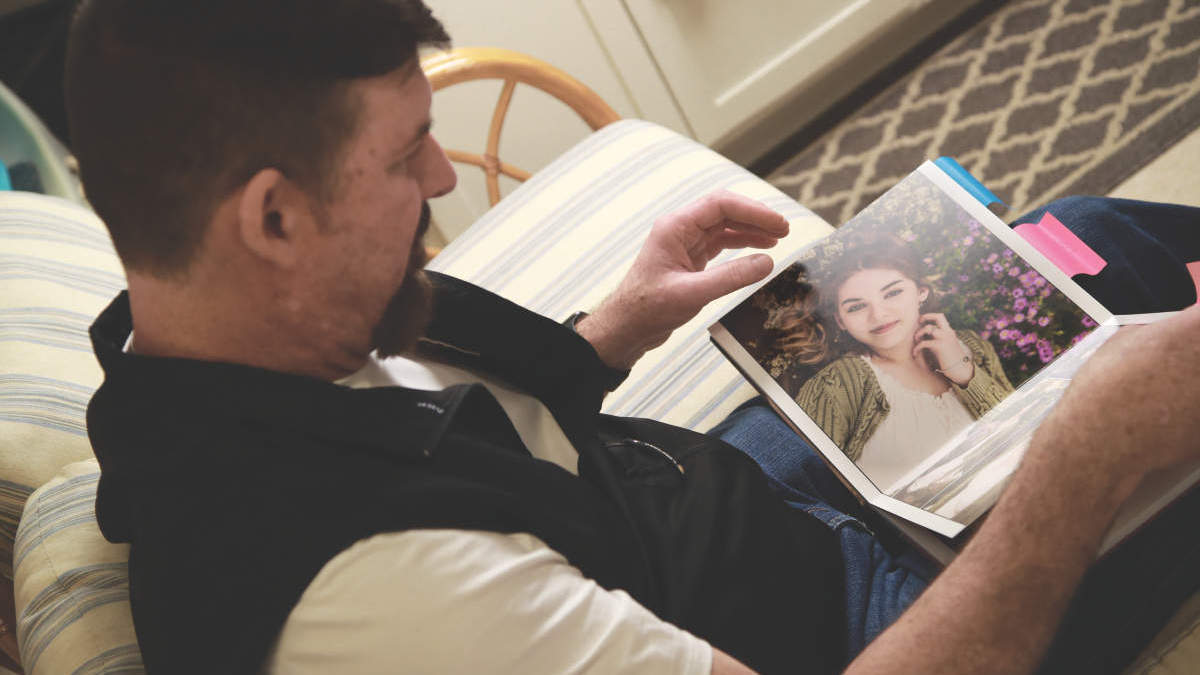

The first child cured of leukemia with CAR-T cell therapy set off a revolution in treating pediatric cancer. The therapy has since helped thousands of patients live longer. But for her parents, Tom and Kari Whitehead, getting their daughter back wasn’t enough. They tirelessly continue to help cancer patients access treatment and raise funds for research to help more patients achieve long-term remission.

Standard treatment had failed our daughter Emily twice. She had cancer for the third time and they were ready to send us home on hospice.

Tom Whitehead

Co-founder, Emily Whitehead Foundation & Lead Lineman at Penelec

Co-founder, Emily Whitehead Foundation & Lead Lineman at Penelec

Emily was able to become the first child in the world with her immune system trained to beat her cancer with CAR T cells.

Tom Whitehead

Co-founder, Emily Whitehead Foundation & Lead Lineman at Penelec

Co-founder, Emily Whitehead Foundation & Lead Lineman at Penelec

Since Emily got better, we've been doing whatever we can to pay it forward to help other families have the same outcome that we've had.

Tom Whitehead

Co-founder, Emily Whitehead Foundation & Lead Lineman at Penelec

Co-founder, Emily Whitehead Foundation & Lead Lineman at Penelec

When you save a child, you save a family.

Tom Whitehead

Co-founder, Emily Whitehead Foundation & Lead Lineman at Penelec

Co-founder, Emily Whitehead Foundation & Lead Lineman at Penelec

May 2023